Summary:

This piece marks the nine-year anniversary of my return to Moyaone — the sacred Piscataway burial grounds — and the passing of my grandmother on November 14, 2016. It continues the work of the Piscataway DNA Project, tracing the Beaven–Brent–Dorsett–Culver lines back to the earliest English–Piscataway alliance in 17th-century Maryland. Drawing on DNA findings, colonial military records, land patents, tribal history, and lived ceremony, this essay situates my ancestor Charles Beaven within the same Patuxent–Potomac corridor where the Tayac forged alliances and where the 1666 Articles of Peace were enacted. It weaves memory, genealogy, and historical truth into a single narrative — a story of rediscovery in the face of centuries of erasure. Following the guidance of the Tayac family and the teachings of Moyaone, this work honors the ancestors, recognizes the still-evolving story of the Piscataway people, and invites descendants to reunite across faith, land, and blood.

Building the sweat lodge before Feast of the Dead on Piscataway burial grounds with our relatives from the south. Turkey Tayac's resting place in background.

By Asher Underwood | Legend of Mary Kittamaquund Project

November 14, 2025 — Nine Years Since the Return to Moyaone

This is the follow-up essay to “Bridging 2014 and 2025: Re-Mapping the Beaven–Piscataway Line from DNA, Documents, Lived Experience and Ceremony,” published in honor of Native American Heritage Month. There will be revisions to this story — probably many — but I need to release this version now, because this week is a sacred week to me.

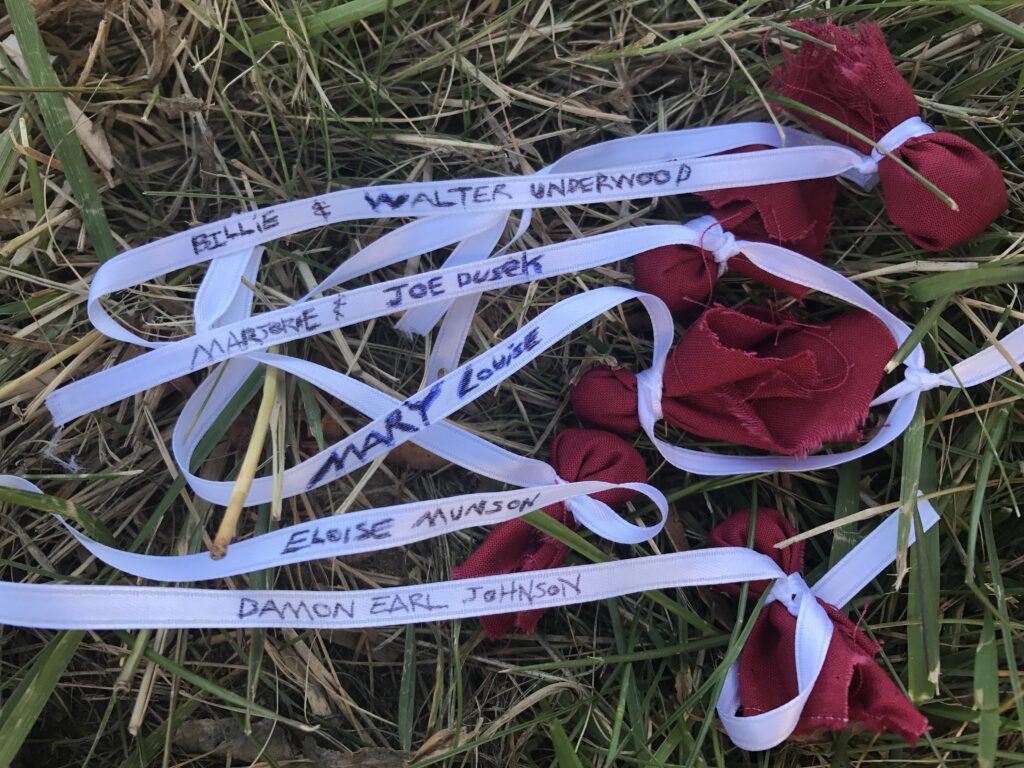

Nine years ago, I stood at the crossroads of life, death, memory, and decision. On November 14, 2016, my maternal grandmother — my "Mimi" — Marjorie “Gilliam” Wiggins Dusek, passed away. She carried an almost unbroken matrilineal line descending from my eighth-great-grandfather Charles Beaven's daughter Catherine "Beaven" Culver.

Two days before she died, on Saturday, November 12, 2016, I joined a sweat lodge at Moyaone, the sacred burial grounds of the Piscataway people — an ancient ossuary where the Feast of the Dead ceremony is still held to honor the ancestors, and where Chief Turkey Tayac is buried through an act of congress. On Sunday the 13th, I had the honor of participating in the 2016 Feast of the Dead ceremony as a guest of the Tayac family.

Then on Monday, November 14, we visited St. Ignatius Church, the oldest continuously active Catholic parish in the country — the same church whose baptismal records preserved Piscataway identity through centuries of colonial erasure.

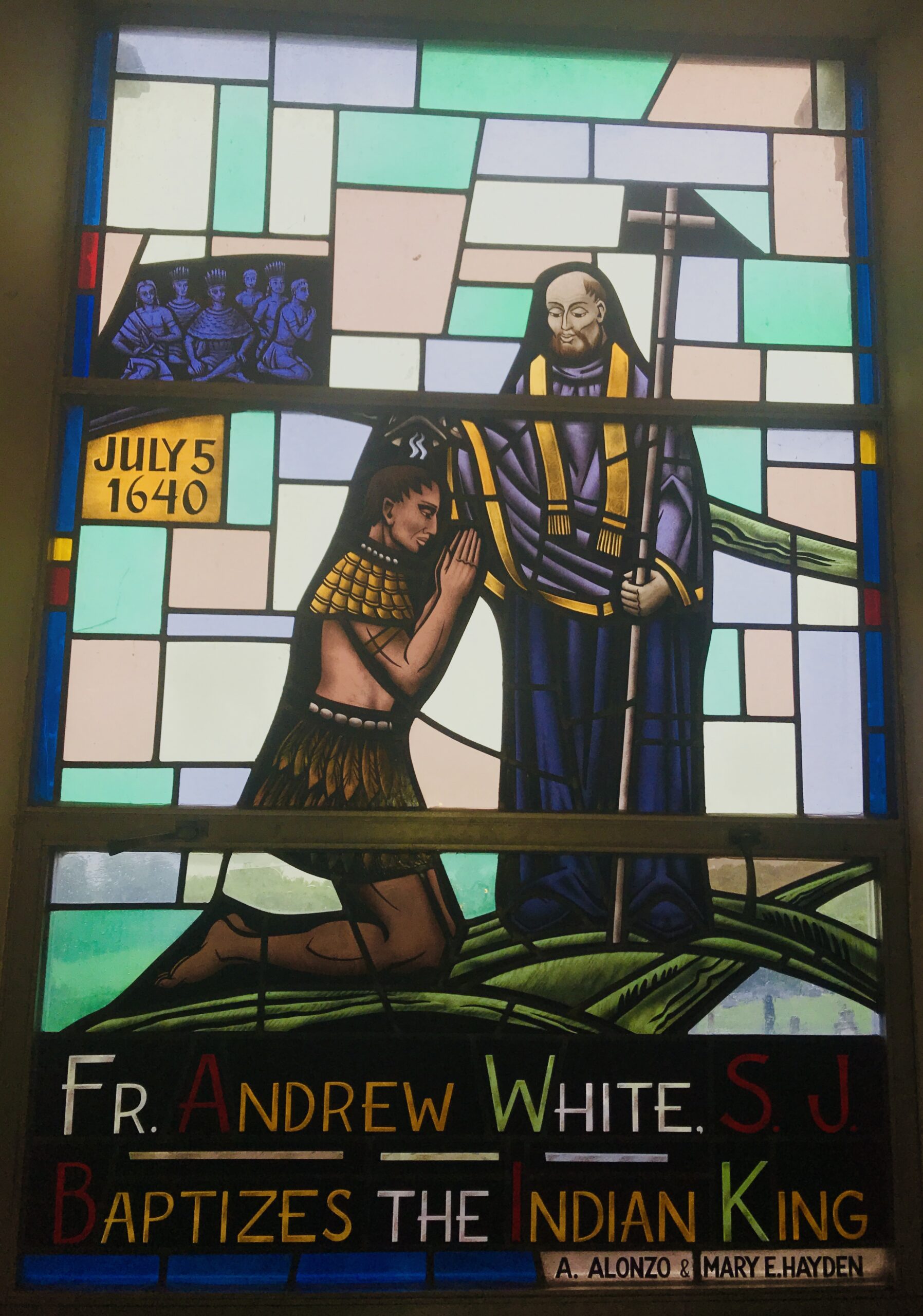

As I stood inside that church, looking at the stained-glass depiction of Kittamaquund’s baptism, my grandmother passed from this world to the next. I still have the timestamp in my camera’s footage of the hour and minute she transitioned. It felt like time folding in on itself — or like the ancestors were calling home one generation while awakening another.

Why this awakening came so late in my life, I do not know. But I know it has profoundly shaped each day since..

Since that day, I haven’t cut the remaining hair on my head, which I braid in remembrance of them. Sometimes my friends crack jokes, but for me it has been nine years of remembering. Nine years of reconnecting. Nine years of walking between history and spirit, watching as more and more people begin to rediscover the names, faces, and stories of those who built Maryland before it was Maryland.

And so this post — published initially November 14, 2025 — is not only a continuation of the Piscataway DNA Project.

It is my nine-year reunion piece.

A return to the ground where at least part of my story, and this story, began to unfold.

My maternal grandmother Marjorie Gilliam/Wiggins Dusek aka "Mimi" December 2, 1925 - November 14, 2016.

A Circle That Never Broke

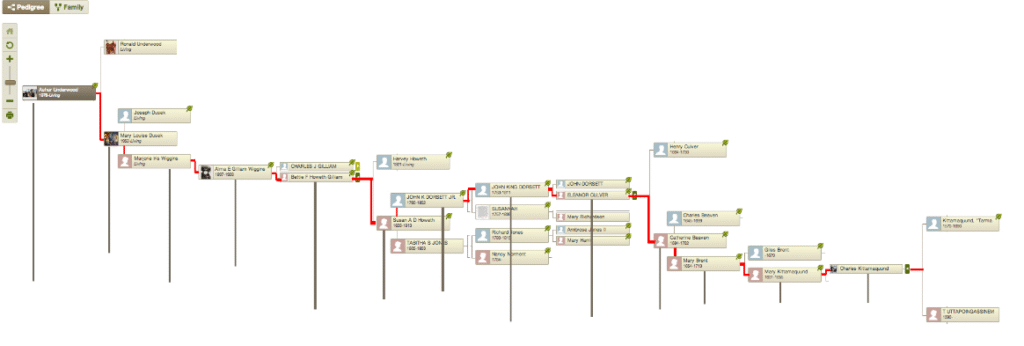

The 2014 Potter Study first identified a shared Native-American genetic signal among descendants who are believed to be traced back to Mary Kittamaquund, daughter of the Piscataway Tayac. My own line descends through Charles Beaven, connecting into the Beaven–Brent / Culver–Dorsett families — the same corridor where the Piscataway–Catholic alliance was first forged in blood and baptism.

A decade later — with new DNA tools, fresh one-to-one kit comparisons, updated research methods, and deeper ceremonial and historical context — that connection is stronger than ever.

But the real significance is not the data.

It’s what the data reconnects:

relatives, memory, land, and responsibility.

The Double Descent

My Beaven lineage appears twice.

Through Ann Beaven (1641–1721), who married John Dorsett Sr., and through Charles Beaven (1645–1699), whose wife has long been believed to be Mary Brent, daughter of Mary Kittamaquund. My ancestral lines converge again in the 1700s through Eleanor Culver and John Dorsett (1723–1796).

These names once marked the Catholic frontier of what would become Prince George’s County — plantations like Hickory Thicket, The Farme, Littleworth, and His Lordship’s Kindness. Their lands rested along the Patuxent, where Catholic families and Piscataway allies together held the frontlines and supply routes of Lord Baltimore’s borderlands.

A Corridor of Alliance

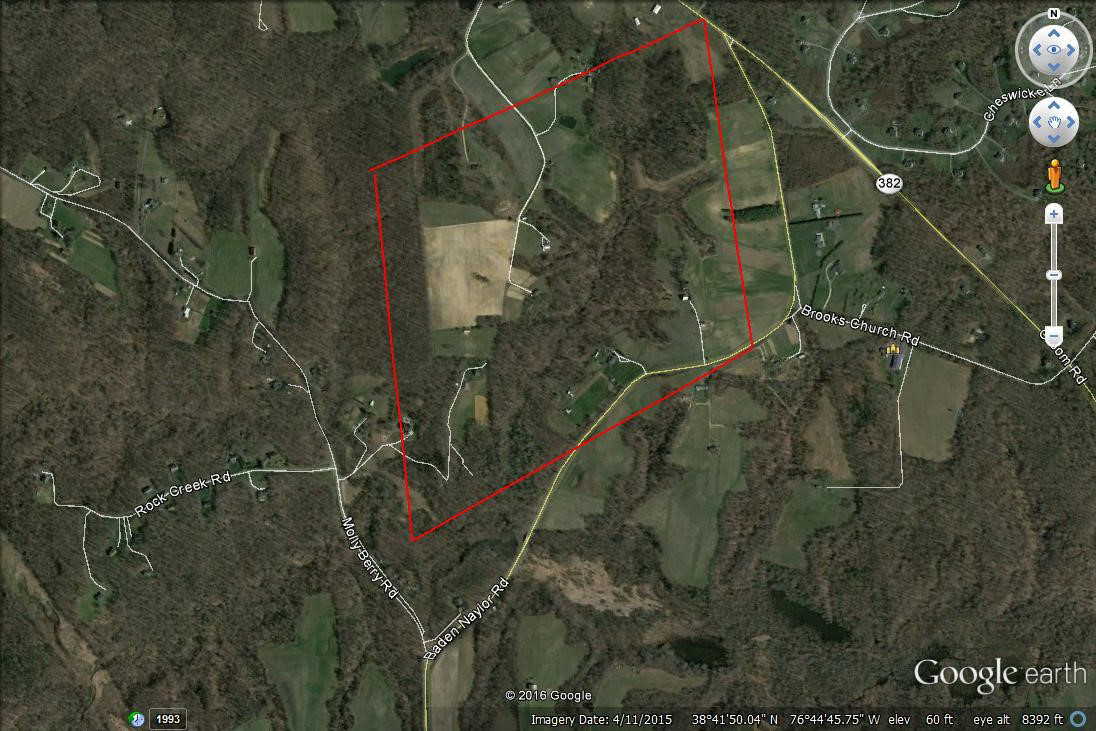

The Beaven and Marsham plantations stretched along the North Branch of the Patuxent River, in what is now Rosaryville State Park and Joint Base Andrews.

The transformation of Hickory Thicket into the heart of modern Andrews feels almost poetic — the ground that once housed colonial forts, frontier musters, and militia routes now safeguards Air Force One and the White House itself.

Maryland Council Proceedings from the 1660s record joint military operations with the Piscataway Tayac, crossing the Potomac into land that would later become Mount Vernon, the estate George Washington built upon territory once held — and often contested — by the Nanticoke and Doeg.

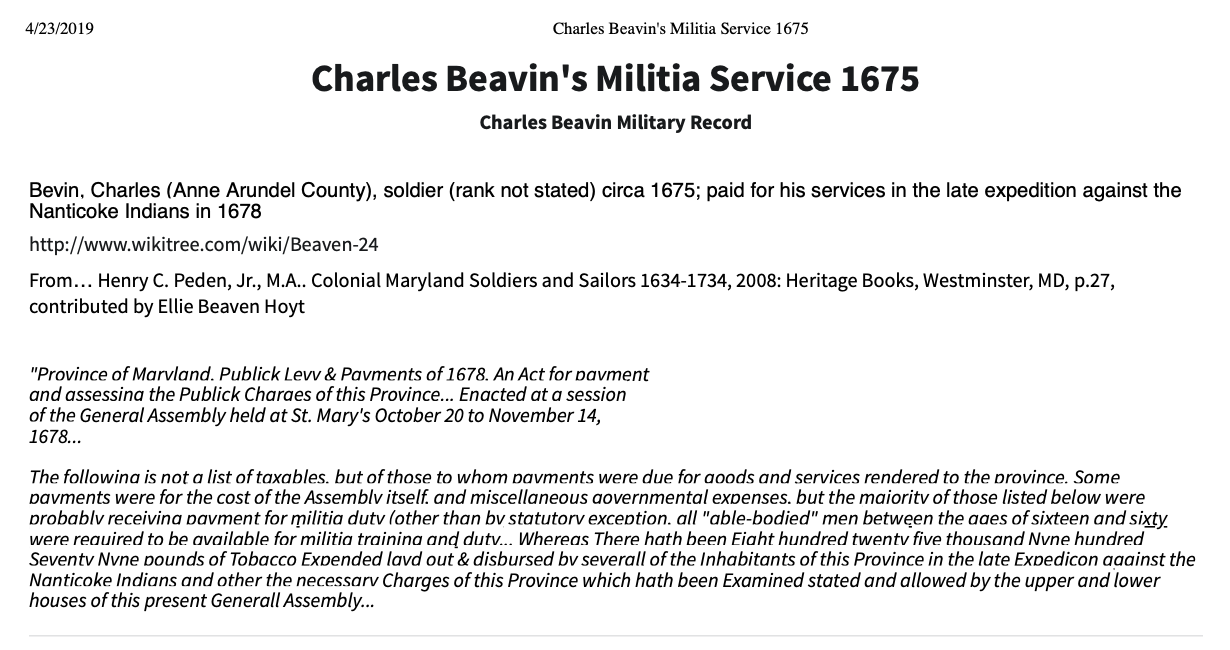

The Militia Record

Families like the Brents, Beavens, Marshams, and Dorsetts appear throughout the same records of frontier defense and Catholic settlement. And this part is not speculative but documented.

My ancestor Charles Beaven served as a soldier in the Maryland militia.

According to Henry C. Peden Jr.’s Colonial Maryland Soldiers and Sailors 1634–1734, Charles Beaven was:

“paid for his services in the late expedition against the Nanticoke Indians” (1675–1678)

This places him directly inside the English–Piscataway defense corridor, during the exact years Maryland was formalizing the Articles of Peace and Amity (1666) with the Tayac. He later assigned his 1666 headright to Capt. Lionell Paully, further tying him to the militia command structure.

This positions the Beaven line (my line) squarely within the lived geography, political world, and military structure of the English–Piscataway alliance. According to Seib and Rountree, when the First Intercontinental War broke out in 1680 between England and France, the Maryland English determined it would be best for the remaining native communities in Southern Maryland to be "consolidated into one, well-defended entity." The governor ordered the Piscataways to destroy their original fort on Piscataway Creek (to prevent the enemy from using it), and move to Zekiah where the new fort was built.

The Brents and the Tayac

At the heart of it all is the story of Mary Kittamaquund, the Tayac’s daughter, who was baptized and married to Giles Brent in 1641. Their union has often been portrayed as a political and religious bridge between the Piscataway and Maryland’s Catholic settlers — but it was also deeply unequal and foretelling.

Historical records make clear that Mary was only about nine years old, while Brent was in his thirties. His intentions were not purely spiritual or diplomatic, as numerous early Maryland histories state this plainly. As summarized by the Kent County Historical Society — echoing colonial accounts:

“Giles Brent married the Indian princess of the Piscataway, expecting thereby to claim their country as his inheritance.”

This was not an innocent union. It was a colonial strategy; and it was in the 17th century, not the 7th century, for those who reason.

What the record framed as alliance was, in reality, dispossession — and a turning point that set in motion centuries of erasure that followed.

Even as Mary’s name entered the English record, much of her family’s story disappeared. Tayac Kittamaquund had other wives and children before his conversion — family lines that continued quietly, without recognition or written history. We may never know the truth of Kittamaquund's lost children or his brother Wannas, who (like Kittamaquund himself) was allegedly killed by poisoning in an act of fratricide. The symmetry of this story to that of Jesuit conspiracy theories and assassinations, is worth exploring at least from a symbolic and colonial context. This most certainly was a geopolitical and clandestine war for power on the new Tiber.

Whatever the truth behind these narratives, I know my ancestors lived, traded, and served within the Piscataway orbit, where bloodlines and alliances converge — and where the story of Maryland was truly born.

From Hickory Thicket to Andrews

It’s not lost on me that Hickory Thicket, once a defensive frontier outpost, now lies directly beneath the flight path of Andrews Air Force Base. The land that trained colonial militias now launches global missions, (depending on your perspective) a continuity of:

- vigilance (or violence),

- protection (or occupation),

- guardianship (or desecration).

The modern landscape of Piscataway Park corresponds almost perfectly to the 17th-century heartland of the Piscataway Tayac. The Beaven, Marsham, and Dorsett estates along the Patuxent formed part of the same network that would have supplied the campaigns against the Nanticoke and Doeg.

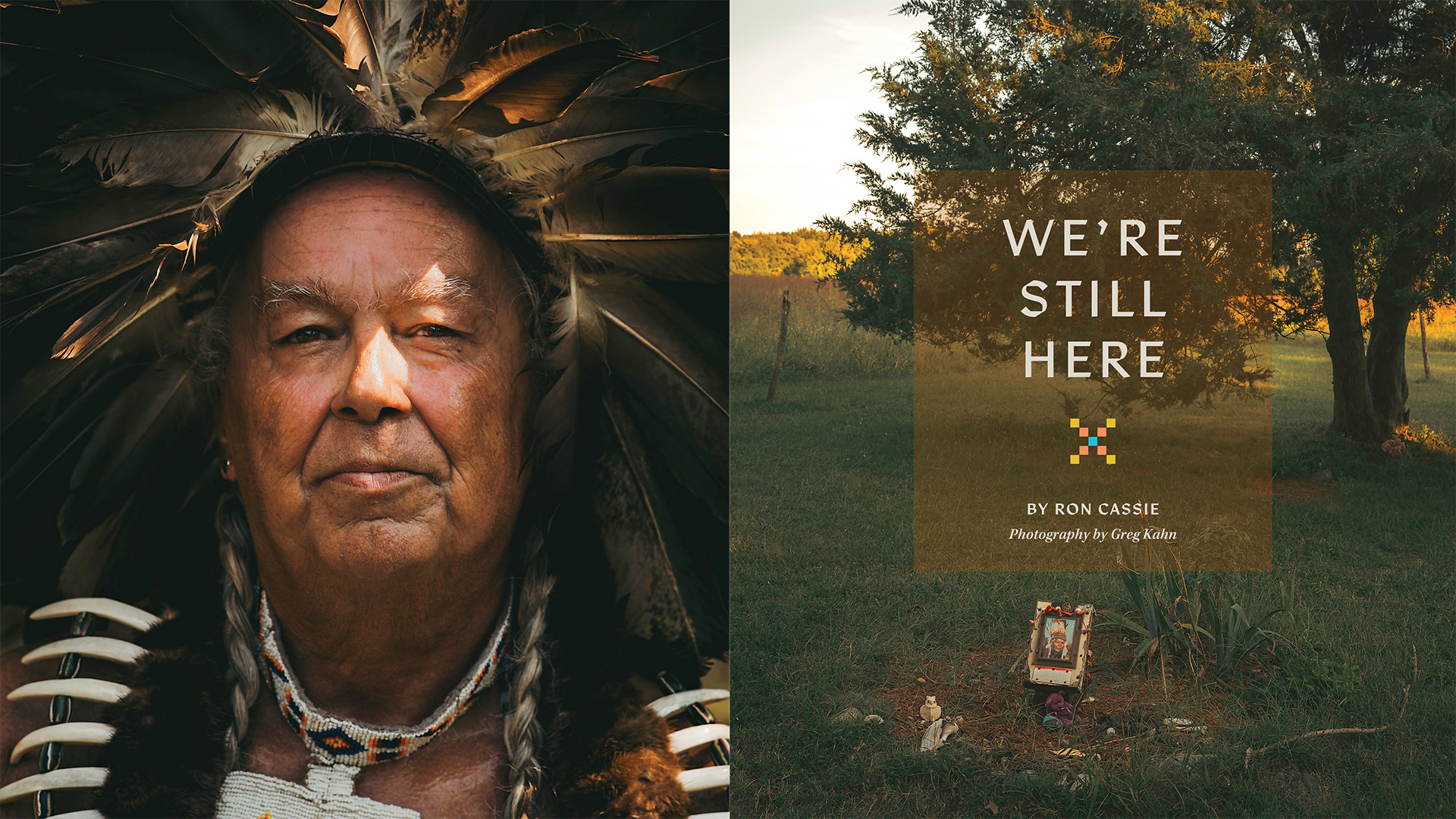

As Chief Mark Tayac recently said in Baltimore Magazine (Ron Cassie, 2025):

“When you look across the Potomac River from the village of Moyaone, you see George Washington’s home, Mount Vernon… He and members of the surviving Piscataway Nation want Marylanders to know there’s still an evolving story too.”

Photo from Greg Kahn for Ron Cassie's piece "We're Still Here: The Still-Evolving Story of the Piscataway Nation for Baltimore Magazine (linked).

Nine Years of Return

When I sweat at Moyaone, I could feel the ancestors all around us.

The songs, the drums, and the living prayers rising from the ground where the Feast of the Dead has been held for generations — have a way of bending time.

As Gabrielle Tayac said:

“For a while, we as Piscataway people are back in our ancient home, with our ancestors and with the living. That is how we come full circle.”

This is what November 12–14 means to me.

Not only the anniversary of my grandmother’s passing, but a time when the veil thins, and I feel the ancestors shifting with the changing season.

Truth, Land, and Rembrance

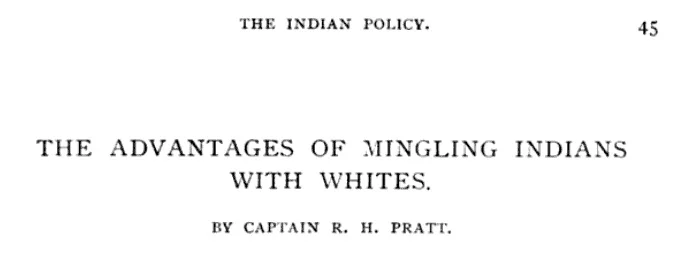

There is a phrase that haunts the history of this continent: “Kill the Indian, Save the Man.” Coined in the late 19th century by Captain Richard Henry Pratt, architect of the boarding school system, it described a policy whose purpose was to erase Indigenous identity, culture, language, memory, and land stewardship while preserving only a colonial version of the assimilated “man” who remained. In my ancestor’s case, that erasure did not happen in a boarding school — but centuries earlier, through baptism, marriage, militia service, frontier alliances, and racial reclassification. The result was the same: ancestors absorbed into the colonial fabric, their Native identity silenced, dissolved, fragmented, or hidden in plain sight.

So this remembrance; including the work of DNA, documents, land, spirit, and ceremony, is not about claiming a convenient ancestry or performing identity. It is the opposite. It is about truth-telling, about repairing the consequences of forced forgetting, and about returning a story to the land and people from which it was taken. It is also about putting distance — respectfully but definitively — between this research and the superficial “family lore” model that turned Native ancestry into a political costume or "Cherokee Princess". This is not an “Elizabeth Warren” footnote, but a documented, lived, and continually verified process rooted in land truth, ceremony, and a call toward justice.

What I seek is not identity. I'm grounded in me.

What I seek is relationship, responsibility, accuracy, and preservation of legacy.

To remember is to participate in the repair and reparations.

To name the truth is to undo a little of the forgetting and double standards that have plagued Native heritage or ancestry.

And to reconnect with the places where our ancestors lived, served, prayed, or were buried is to stand at ground zero where justice and reconciliation begins.

A Reckoning With the Record

As “We’re Still Here” recounts, the war against the Piscataway began as early as 1639, when Governor Calvert declared them “enemies of the province.” By 1666, the so-called Articles of Peace and Amity required the Piscataway to disarm on sight, under penalty of being legally shot and killed.

“All were trampled in the end.”

— Ron Cassie

“The onslaught and genocide … occurred in Maryland two centuries before the Trail of Tears.”

To have ancestors on both sides of that history is not an easy inheritance.

But truth is what allows healing.

People often ask,

“You have thousands of ancestors at ten generations back — why focus on one native line from nearly four centuries ago?"

Because the opposite of remembering is forgetting.

Because Mary Kittamaquund is the story of Mary-land, and "Mary" was the name my grandmother gave my mother.

And because, as we say when entering the sweat:

Mitákuye Oyás’iŋ — for all of our relations.

This matters.

Records of Erasure and Recognition

Ironically, it was Catholic baptismal records — especially those at St. Ignatius Church — that by chance helped preserve Piscataway identity when government censuses erased it by reclassifying Native families as “mulatto” or “Negro.”

Those fragile parish entries helped support Maryland’s 2012 recognition of both the Piscataway Indian Nation and the Piscataway Conoy Tribe.

Faith, blood, and memory have always intertwined here — and for me, they converge on November 12–14. Even my eldest daughter Kaya was baptized at St Ignatius.

Kaya's Baptism at St Ignatius on May 12, 2019

Seeking More Clues — and More Relatives

Whether Charles Beaven’s Mary proves to be Mary Brent or another descendant of Kittamaquund’s extended family, the Beaven–Marsham–Dorsett network tells one woven story:

Welsh Catholic, possibly Quaker, and Piscataway ancestry interlaced across Maryland’s founding families — including descendants of the forgotten, and descendants of the formerly enslaved.

The circle is wider than we think.

Chief Mark Tayac’s Four Points

In his 2023 State of the Nation address, and referenced in "We're Still Here: The Still-Evolving Story of the Piscataway Nation for Baltimore Magazine", Chief Mark Tayac named four living goals for his people:

- Repatriation of ancestral remains.

- Return of public lands to Indigenous stewardship.

- Creation of community centers for Piscataway families.

- Training & resources for “the next generation still to be born.”

These same themes — restoration, preservation, renewal — guide this research as well.

Full Circle

Before his passing, Chief Turkey Tayac told his family:

“Bury me there at Moyaone, and I can help you forever.”

Every time I return — in mind or in body — I feel that promise. His spirit, and the spirits of all who rest in that sacred ground, continue to guide those still listening.

It is as if the land itself remembers, whispering through the cedar and the river that this story was never over — and, as Chief Mark Tayac said, is “still evolving.”

The story of Mary Kittamaquund is, in truth, the story of Mary-land.

And as we say entering the sweat:

Mitákuye Oyás’iŋ — for all of our relations.

To be continued…

Citation Appendix

Legend of Mary Kittamaquund Project

Prepared November 2025

Primary Sources

Colonial Military Records

-

Peden, Henry C., Jr. Colonial Maryland Soldiers and Sailors 1634–1734. Heritage Books, 2008.

— Entry for Charles Beaven (Anne Arundel Co.), “paid for his services in the late expedition against the Nanticoke Indians,” c. 1675–1678.

Maryland Council Proceedings (1650–1670)

-

Archives of Maryland Online, Vols. 3–5. Proceedings documenting the Doeg/Nanticoke conflicts, Piscataway alliance, and militia campaigns along the Potomac.

Land Records & Patents

-

Maryland Patents, Libers 5–10, Maryland State Archives.

— Entries for Hickory Thicket, The Farme, Littleworth, His Lordship’s Kindness, and adjacent tracts along Patuxent.

St. Ignatius Church (Port Tobacco)

-

Parish Baptismal & Marriage Registers (17th–19th c.).

— Records documenting Piscataway descendants under the classification “Indian.”

Secondary Sources

Tayac Family Histories

-

Tayac, Gabrielle. Personal Essays on Piscataway Culture, including “Feast of the Dead” reflections.

Piscataway Ethnohistory

-

Clark, Ella. Indians of the Chesapeake Bay Region. Smithsonian Folklife Studies.

Ron Cassie, Baltimore Magazine

-

“We’re Still Here,” Baltimore Magazine, November 2025.

— Interviews with Mark Tayac, Gabrielle Tayac; historical analysis of Piscataway lands & state recognition.

Seib, Wayne E., and Helen C. Rountree

- Indians of Southern Maryland.

Solomons, MD: Calvert Marine Museum Press, 1996.

DNA & Genealogical Studies

Shawn & Lois Potter

-

“Analysis of Shared Native American DNA Signals in Beaven–Brent Descendants.”

Private circulation, 2014; updated notes 2020–2024.

Personal DNA Testing

-

GEDmatch One-to-One comparisons, triangulation notes (Beaven–Brent–Culver–Dorsett clusters).