Every so often, a sincere question opens a doorway: not to argument, but to understanding.

One of the most important questions in the study of early Christianity is this:

How do we determine the earliest, most historically grounded understanding of who Jesus was?

Historians don’t answer this by starting with later creeds or theological conclusions. They look instead at the earliest sources, the earliest communities, and the religious world Jesus himself lived in.

What emerges is not a modern debate, but a consistent historical pattern; one that deserves to be examined carefully.

Below is a summary of the core ideas that emerged, written here as a resource for anyone curious about the Jewish, Christian, and Islamic picture of the Messiah.

1. What do the earliest Christian layers actually show?

Historians don’t rely on one book or one tradition. They compare independent sources that trace back to the earliest period before later theology took shape:

-

The Gospel of Mark, the Q source (aka The Sayings Gospel), and the Gospel of Thomas preserve early sayings of Jesus.

-

The Dead Sea Scrolls world reflects the Jewish context Jesus lived in: strict worship of God alone.

-

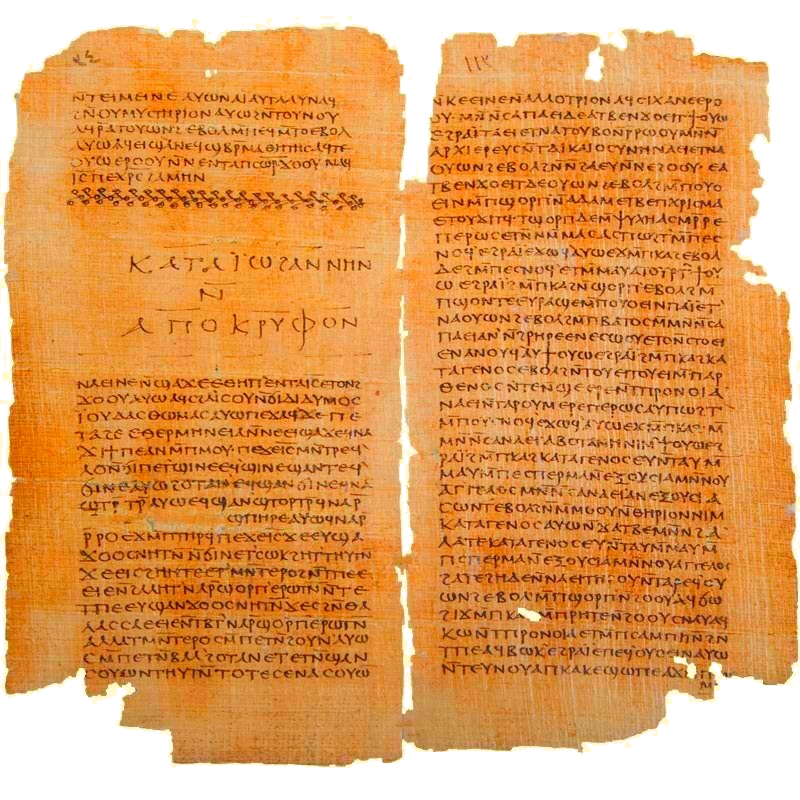

Nag Hammadi library, though copied later, preserve pre-Pauline patterns where Jesus guides people to God, not to himself.

Across these early layers, one pattern is unmistakable:

Jesus prays to God, worships God, and teaches others to worship God.

None of these early traditions present Jesus as the object of worship.

2. Where does the idea of “praying to Jesus” begin?

When people argue that Christians prayed to Jesus before Paul, they often cite:

-

Later Church Fathers

-

Second-century Christian liturgies

But historically speaking:

-

Acts is written decades after Paul, by an anonymous author.

-

The first appearance of “Maranatha” is in Paul’s own letter (54 CE).

Using Paul’s letter to prove something happened before Paul is circular.

We simply do not possess any independent 30s CE text showing followers praying to Jesus.

This isn’t anti-Christian; but rather it is the consensus of biblical scholarship.

3. Mediator ≠ Deity: What Nag Hammadi actually says

A key moment in our conversation was the quotation of a Nag Hammadi prayer:

“I invoke you … through Jesus Christ, the Lord of Lords, the King of the ages; give me your gifts … through the Son of Man, the Spirit, the Paraclete of truth.”

This is beautiful.

But it does not show Jesus being worshipped as God.

It shows the ancient Jewish pattern:

God is the One prayed to; the messenger is the mediator.

That’s the same pattern as Moses, Isaiah, and every biblical prophet. It's also important to recognize that the concept of "Son of man" pre-dates Christianity in ancient Judaism.

Nothing in Nag Hammadi replaces God with Jesus.

4. The Paraclete: Where Judaism, Christianity, and Islam meet

The word Paraclete (paraklētos) means:

-

advocate

-

helper

-

comforter

-

intercessor

In early Judaism, this theme appears often: God sends a helper or advocate to guide His people.

Early Syriac Christians interpreted the Paraclete not as a divine person, but as a future messenger; a final teacher of truth.

Islam sees this as a prophecy of the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ, whose role matches the ancient meaning of “advocate/comforter.”

This explanation actually aligns with:

-

earliest Christian expectations

-

the Semitic worldview Jesus lived in

—not later Greek metaphysics.

5. Islam’s portrait of Jesus: The earliest pattern preserved

In the conversation, the question finally came up:

Where does Islam get its picture of Jesus?

Here is the answer in its simplest form:

-

The Qur’an is a 1400-year unaltered Arabic text, preserved through mass memorization; the same Semitic oral tradition the Israelites used.

-

Arabic and Aramaic are sister languages of the same Semitic Language Family; Jesus’s own word for God was Alaha/Allah in East-Syriac.

-

The Qur’an presents Jesus exactly as the earliest Christian strata do:

-

honored and chosen—

-

but not divine and not the object of worship

Islam doesn’t introduce a new Jesus.

It preserves the oldest one.

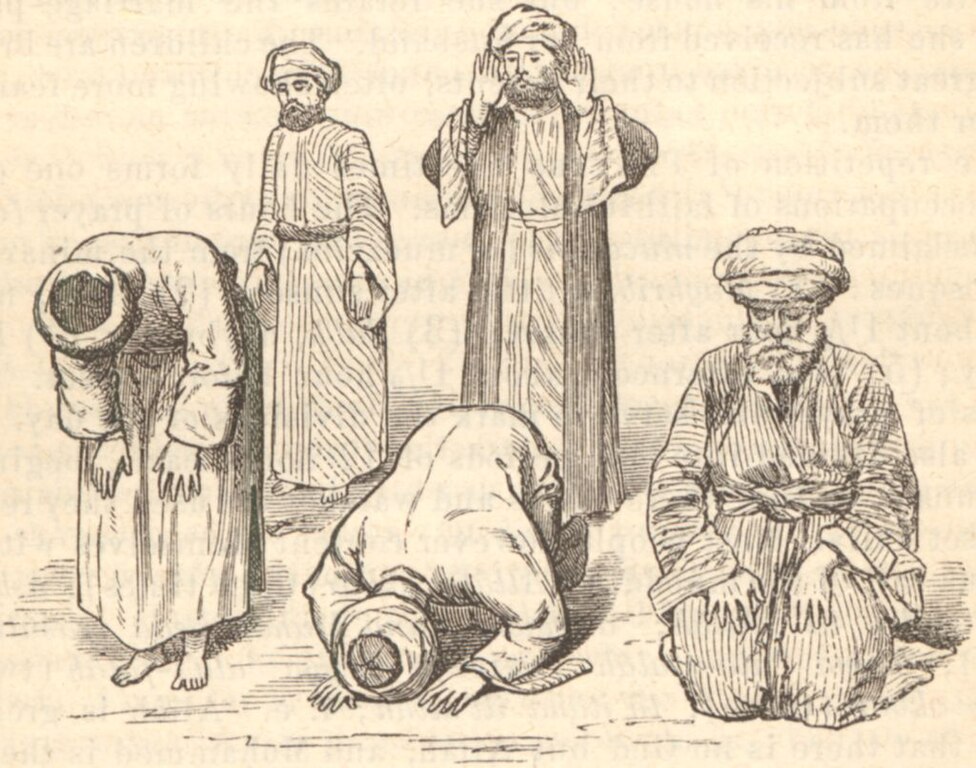

A Jesus who:

-

prays with his face on the ground (as the Syriac Christians did)

-

worships the Father

-

never tells anyone to worship him

-

and never prays to himself

This is the Jesus of the Dead Sea Scrolls world, of early Christian sayings, of the early Semitic church.

One of the clearest examples appears in the earliest Gospel, the Gospel of Mark:

“Going a little farther, he fell on the ground and prayed that, if possible, the hour might pass from him. And he said, ‘Abba, Father, all things are possible for You…’”

(Mark 14:35–36)

This posture, falling face-down in prayer; is the traditional Jewish posture of submission before God.

Jesus is not praying to himself.He is praying to the Father, addressing God as Abba, just as the Hebrew prophets did before him and as Syriac Christians and Muslims would later continue to do.

6. The Earliest Followers of Jesus: The Ebionites and the Nazarenes

Long before later doctrinal developments, Jesus’ earliest followers were Jewish believers who continued to worship God alone.

Two of the most important early groups were:

• The Nazarenes – Jewish Christians who accepted Jesus as the Messiah but maintained strict monotheism and continued to observe Jewish law.

• The Ebionites – an early Jewish-Christian movement that explicitly rejected the idea of Jesus as God, viewing him instead as a human prophet chosen and empowered by God.

Church historians such as Irenaeus, Origen, and Epiphanius mention these groups—not as outsiders, but as remnants of the earliest Jesus movement.

These communities:

Worshipped God alone

Saw Jesus as the Messiah

Rejected prayers directed to Jesus

Preserved a Semitic, non-Greek understanding of God

Their beliefs align closely with the earliest Gospel traditions and with the Jewish religious world Jesus himself inhabited.

7. Why this matters for Dawah

This entire dialogue revealed something beautiful:

The Islamic picture of Jesus is not a “correction” of Christianity—

it’s a return to the earliest, most historically grounded understanding of who he was.

Islam honors Jesus not as God, but as:

-

the Messiah,

-

the Word God sent,

-

a prophet who points us back to the One who sent him.

And it keeps intact the same strict monotheism Jesus himself lived and preached.

This is not an attack on Christianity.

It’s an invitation to look at Jesus through the lens of the earliest history, not later doctrinal developments.

An invitation to… tawhid—the worship of God alone.